|

Until the 1950s, Malga Ramezza Alta, a 1485 metre high peak in the Le Vette group in Belluno Dolomites National Park, was of strategic importance for the short summer mountain pasturing of animals in the areas overlooked by the Sasso di Scàrnia. Herdsmen would bring here their cattle, a source of meat and dairy products. They used to leave the long Valle di San Martino with their animals and climb up to the pastures, fragrant in summer with the scent of grass and flowers, and then stay for nearly three months in the Val Fratta. During this time they would lead a Spartan life, living close to nature. With industrialisation, summer pasturing declined. All the toil and hardships it involved led herdsmen to keep more and more to the lower areas and use the plains rather than the uplands. Use of the casère (Alpine refuges), shepherd’s huts and mountain activities in general therefore went into decline, along with haymaking, summer pasturing in the mountains, woodcutting and other activities; and this led to the abandonment of the mountains for quite a number of years, leaving them to hunters and the odd hiker. Malga Ramezza Alta also suffered this fate, and within a few years had declined. Then, in the1980s, a group of volunteers from Vignui decided to do something about the situation; but it wasn’t until 1988 that a group of hikers from the Feltre area, who knew the area of the “malga” (Alpine shepherd’s hut) well, got together with a similar group calling itself “I Camòrz” with the aim of bringing life back to Malga Ramezza Alta. This is at strategic point on High Altitude Trail No. 2, connecting the Rifugio Dal Piaz with the Rifugio Boz, and an important base camp for anyone climbing from the Valle di S. Martino, which until recently was very rarely visited.

There were two stages in the restoration job: the first of these involved physically carrying tables, poles, iron bars, sheet metal, cement (sand was obtained from the bed of a stream running near to the shepherd’s hut), guttering, furnishings and all the equipment that had to be taken up the mountain and down again after use. One memorable Sunday, there were about fifty people carrying all sorts of things up. They had never seen so many people in the area: children, teenagers, women, men and the elderly, united by the same aims, all working together enthusiastically to rebuild a shepherd’s hut, which meant different things to different people. For some people, they weren’t just rebuilding a disused building, they were bringing to life the history of the place, their roots, traditions and the faded photos of those people: the parents and grandparents who had lived there. It meant finding in those faces their own history; and the meaning of a life lived. The second stage of the job involved six people carrying out the real work of reconstruction. This was completed in 2000; but it wasn’t until 26 October 2001 that the inauguration and Mass took place, with over a hundred people in attendance. Leaning against a typical crag, the “malga” appears in the high Valle di S. Martino between two rocky glacis, with the Pale del’Ai to the east and the Costa Alpe Ramezza to the west, and lies among the pastures, now overgrown with vegetation, below the rocky buttresses of the Sasso di Scàrnia. Two hundred metres further down, along the upward path, we find the old pendana, an open shelter with a roof that served as a cattle shed, but which is now just a wall that snakes like to hide in. In recent years the restoration of the refuge has encouraged hiking in the Valle di S. Martino, making connections and circular routes possible, as well as being a source of income. Its only drawback is the lack of water, which is found 30 minutes away at a spring to the south west, along the Fontanìe path (south east of the Col de la Madona spurs).

These are unforgettable places, where the soft sound of cow-bells was heard and there was a sweet perfume of hay mixed with flowers and other essences. Every path, rock, stone, tree and sign is like a piece of ourselves brought back by remembrance, evidence of a presence that even time itself cannot erase from memory. I like to think that, like St. Martin when he divided his cloak with a beggar, this mountain-loving group of friends has given something of itself to others: their time, sweat and effort; which goes to show that, in addition to everything else, the mountains bring people together and make each member of a group depend on the next.

The “giazzera” of Monte Ramezza

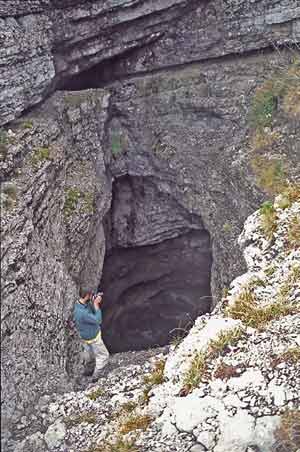

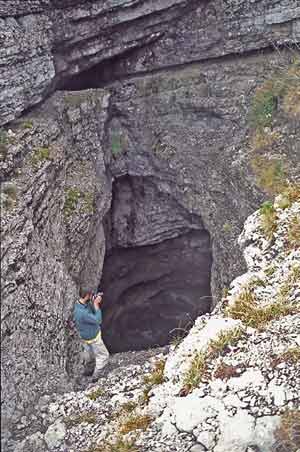

The story of the giazzera (ice cave) at Monte Ramezza began in August 1921, when a group of about fifteen hungry war veterans from Lasèn, a village on the southern scope of Monte S. Mauro (Feltrine Alps), was recruited by two enterprising local figures, Giosuè Miniati and Umberto De Paoli. The aim was to provide ice for the Pedavena Brewery, for the two men had made an agreement with the brewery’s Luciani brothers to deliver 1.5 tonnes of snow-free crystal ice every day to the public weigh house in Pedavena. Payment would be on delivery of the agreed amount, at the rate of 3,500 liras per tonne, which was almost 1,500 liras per tonne more than the going rate for industrial ice. Apparently, the brewery supplied the ice-diggers with 30 strong sacks to cover the ice with during transportation plus a large tree saw. After work, the company would give the workers a snack and two large beers. During the First World War, following the defeat at Caporetto, Feltre and Belluno came under Austro-Hungarian rule and, in 1918, all metals were requisitioned for use in making armaments. Production at the brewery, about 3 million litres a year, ended when they took away the refrigeration plants along with other things. The brewery’s fortunes were therefore linked to the Ramezza cave, which they already knew about in the mid-1800s, and the needs of the poor in the mountain villages. So began the “Summer of ice” for these men who, for about 15 days, went up and down the Valle di S. Martino and the Val Fratta, then the Valòn of the Peròn as far as the Giazzera cave to dig out ice and take it back down. With an ash sledge on their shoulders (about 30 kilograms), they would start off from just after the calchèra (where you can still see the dry stone wall of the old ice store) and climb to the Giazzera, at 1,860 metres. Once there, it was a short descent into the cave and after the cone of snow, you were in the vast ice cavern from which the ice blocks were dug. It is said that, on each trip, they carried down six to eight blocks weighing 35 to 50 kilograms each. They must have had the strength of an ox; and perhaps desperation gave them their strength! Once the blocks were down, they were loaded on wooden ox-carts on which they travelled down to Pedavena, along the Val S. Martino and through the villages of Vignui and Pren. After the first trip, the ice-diggers had a small snack and climbed back up to the Giazzera where they spent the night in the open inside a ravine, under some sheets. Next morning at dawn, they would descend with their load, then climb back and descend once again. It was hard, laborious work made lighter by the idea that each of them would take home a tidy sum to their family, and by the lively atmosphere that filled the region in those days. It is worth remembering that, in addition to the ice diggers, woodcutters, charcoal burners, and the herdsmen with their sheep and cattle, there was the life of the shepherd’s huts (there were at least 15 Ere, or shepherd’s huts, in the valley). In short, it was swarming with faces, voices, laughter, song, stories and chatter that animated and gave

colour to this impoverished world, left behind by a war that had brought the entire economy to its knees. It was a short period, a little-remembered piece of history. Nowadays, only a few especially keen hikers and potholers come to the Giazzera. However, we can still hear echoes of all those comings and goings, with sledges and ice carried on backs; the curses, laughter, groaning and grunting of all those men who had to climb the mountain paths during that short period. Climbing the Valle di S. Martino in the silence of the beech woods, one seems to see and hear those voices once again.

The Church of San Martino in Valle

The church is dedicated to the Bishop of Tours, a Roman soldier who converted to Christianity against his father’s will and who is famous for having divided his cloak with a beggar. His feast day is 11 November, the end of the growing season. That is why, according to tradition, he became the patron saint of hosts, grape harvesters and vine-dressers. In its present form, the oratory, built on mediaeval remains, dates from the end of the 16th century. The spacious nave is covered with frescos in large panels,

badly damaged and difficult to see; however, they seem to be the work of a single artist who, perhaps, finished them before 1594, when the church was consecrated. They depict Scenes from the life of St. Martin and Scenes from the life of St. Anthony of Padova.

Suggestions for Visiting the Malga Ramezza Alta Area The “Giazzera” of Mount Ramezza

A good round trip which allows you to visit this large chasm -whose entrance is at an altitude of about 1,800 metres in the basin that lies between Monte Ramezza (2,250 metres) and Col Veriòl (2,173 metres), hidden between the south eastern spurs of Col de la Madona in a region of Karst gullies -known as the Sfondrà: a large shelter used by shepherds who used to bring their sheep to pasture in the area. Climbing the Valòn del Peròn, the chasm suddenly appears on the left, under the Costa Brusada and hidden between two rocky spurs.

From Valle di S. Martino, a car park at 560 metres, up to just before the Malga Ramezza Alta at 1,485 metres, 2 hours as for itinerary no. 2. Just before the shepherd’s hut, we find the ruins of the Ramezza cattle shed. To the left, near the dry stone wall of the old structure, a track branches out towards the west, pointing towards a patch of mountain pine. On reaching the edge of the mountain pine and the beechwood, we turn right and continue up the steep wooded slope, leaving behind the mountain pine further up. Continuing, we come to the bottom of a low wall and enter what is clearly a canyon, the Valòn del Peròn, partly covered by mountain pine and some rock-pile signposts. Carrying on through mountain pine and strips of thin pasture, we move to the right at the level of a band of rocks. Further up, we start to lose the track among the mountain pine, and climb diagonally leftwards to resume it. After starting up the steep slope topped by a grassy hill we take the track to the top, following the rock-pile signposts up to the opening to the giazzera, suddenly appearing on our left at 1,860 metres, after 1 hour’s hiking. Nowadays, the snow is 8 metres, not 2 metres, from the entrance. Following the rock-pile signposts, from the chasm we proceed up the Karst slope of the Sfondrà, marked by ruts, holes and dolinas, and climb back on to the High Altitude Trail No. 2 at about 2,050 metres, beneath Monte Ramezza. We now turn right, to the east, starting to descend toward the Scarniòn fork at 1,900 metres, where we then turn right and traverse a section of mountain pine that, crossing below the rocky spurs of the Sasso di Scàrnia (2,227 metres), leads to the Forcella di Scàrnia (1,598 metres, 1 hour 15 minutes). This brings you to Malga Ramezza Alta (1,485 metres) in 15 minutes and, as with the uphill trip, back to the starting point in about 1 hour 30 minutes.

Altitude difference: 1,500 metres

Time: 6 hours

Grade: EE

Recommended season: May to October

Base camp: MalgaRamezzaAlta(boarding for 8 places and fireplace)

Access: from Feltre, as for itinerary no. 2

|